“There is infinite amount of hope in this universe … but not for us,” Franz Kafka told us years ago. The aphorism comes from a novelist whose stories include characters that aim for seemingly achievable goals, but almost tragically, never manage to get closer to them. In Pakistan today, Kafka’s quip seems to hold true — for there is hope aplenty in this world, only not for us.

The reference perfectly encapsulates the country’s climate crisis. Pakistan was hit by a number of major climate catastrophes this year, but the most horrifying and fatal of them all were the disastrous floods that engulfed a third of the country. The floods displaced millions of people, destroyed infrastructure spread over thousands of kilometres, wiped out livestock, and decimated crops.

However, five months on, the government’s struggle for rehabilitation, recovery, and reconstruction has the feel of Kafka’s fables.

According to a recent United Nations report, more than 240,000 people in Sindh remain displaced while satellite images show that around eight million people are still “potentially exposed to floodwater or live close to flooded areas”.

The report states that at least 10 districts in the province — Dadu, Kambar Shahdad Kot, Khairpur, Mirpurkhas, Jamshoro, Sanghar, Umerkot, Shaheed Benazirabad, and Naushero Feroze — still have standing flood water. Balochistan’s Sohbatpur and Jaffarabad have reported the same tale.

While receding water has allowed millions of people to return home, they continue to face shortages of essential items such as food and medicine coupled with other challenges brought about by the winter season.

“Flood-hit regions are now tackling health-related challenges,” it added.

Sindh

In Sindh, most people returning home have been forced to live either with their relatives or have found refuge on the roof of their demolished houses.

“We were living at the rehabilitation camp set up in Karachi,” Aftab, a resident of Sukkur told Dawn.com. The young man, who had left a demolished house, two daughters, and a young mother in August and migrated to the metropolis, returned to his hometown earlier this month.

“The state of my town is still the same. Our houses are demolished,” he said, adding that he was forced to live on the roof of his house, which according to him was the least damaged part of his home.

“The government had promised to rebuild our houses but, like always […] when do they ever keep their word,” Aftab added.

Aftab’s concern is not the only problem plaguing Sindh today — the standing floodwater in the province also gives rise to a lot of health issues.

According to a government report, dated Dec 19, nearly 10 million cases of chest infection, 11.7m cases of skin diseases, 1.05m cases of gastroenteritis, and more than 500,000 cases of malaria have been reported in the province since July 1.

The report showed that apart from roof collapse, electrocution and drowning, gastroenteritis has taken the lives of 23 people in the last six months.

Moreover, Imdad Ali — spokesperson of the Liaquat University of Medical Health Sciences — told Dawn.com that there are thousands of cases that go unreported.

Ali has visited nearly 100 medical camps set up by the government in flood-hit areas and has interacted with thousands of patients. “Two weeks back, we visited a camp in the Bakhar Jamali village. The area has reported 32 deaths in the last three months.

“We were sent there by the Sindh government to inspect the camps and investigate reasons for the increased fatalities,” he said.

The spokesperson recalled that when his team reached the site in Matiari district, they found out that the area did not have a single hospital. “The closest medical facility is located 80km away from the city — which is approximately 2 hours if one travels by car.

“So, most of the deaths that take place in the villages go unreported. Even the day we had reached Bakhar Jamali, a 35-year-old man had passed away because of an ‘unidentified disease’ […] the locals said they were taking him to a hospital, but he passed away on the way,” Ali added.

Balochistan

A similar situation, more or less, persists in Balochistan as well. According to the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA), many people in the flood-affected districts of Killa Saifullah, Lasbela, and Jaffarabad are still living in tents set up by the government.

This is because there is still 2 to 3 feet of water standing in their villages and fields, Mir Behram — an activist in Naseerabad Division — told Dawn.com.

“The water in these areas is not drying up because the land is salty and beyond the government’s access,” he said.

Behram explained that most of the people living in tents had returned home. “But back in their hometowns, there is no food or clean water. They have all just gone back with the hope to start rebuilding their houses. Most of them are just literally lying under open skies and sleeping on charpoys.”

Meanwhile, back in the relief tents, a host of diseases have gripped the flood affectees, the most prominent of which are malaria, mumps, and cholera.

But the most cases were those of malaria, the activist said. “You can say there is an outbreak.

“Just 15 days back, I visited a flood camp in the Kachhi district. We conducted tests of 250 people — both children and adults — and the results showed that 95 people had tested positive for malaria.”

However, PDMA spokesperson Younas Mengal insists that the health situation in the province has “improved now”.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Earlier this year, when the floods hit the country, it was the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa that had first fallen prey to the gushing waters.

Videos in August and September had shown hotels, houses, roads and even bridges being gulped down by the gliding waves, one after the other. The infrastructural damage was massive.

Today, while there is no standing water in the province, cruel winters have made life difficult for the flood victims. Locals say most of the people who lost their houses are now forced to stay in tents in temperatures falling below freezing point.

Muhammad Ali Chapli, a resident of Khouzh village in Upper Chitral, told Dawn.com that during the floods, nearly 80pc of the infrastructure in his village was destroyed. “Dozens of houses were reduced to rubble and agricultural land spread across hundreds of acres was ruined.

“But no one came to help us. We did everything on our own, from rebuilding roads to our homes,” he said.

When the calamity hit the province, both the local and federal governments announced compensations for the people whose houses had been completely or partially damaged. As per statistics available on the KP government’s website, so far, Rs3.5bn have been dispersed.

However, residents complain that they haven’t received the money yet.

Zubair Torawali told Dawn.com that in his town of Bahrain, rehabilitation is “next to none”. “During the floods, 1,200 houses in our area were destroyed. Not even one of them has been repaired yet.

“The only thing that the government did was the reconstruction of the Bahrain-Kalam Road. But ever since those repairs have been done, we have seen an increase in accidents on the road,” he said.

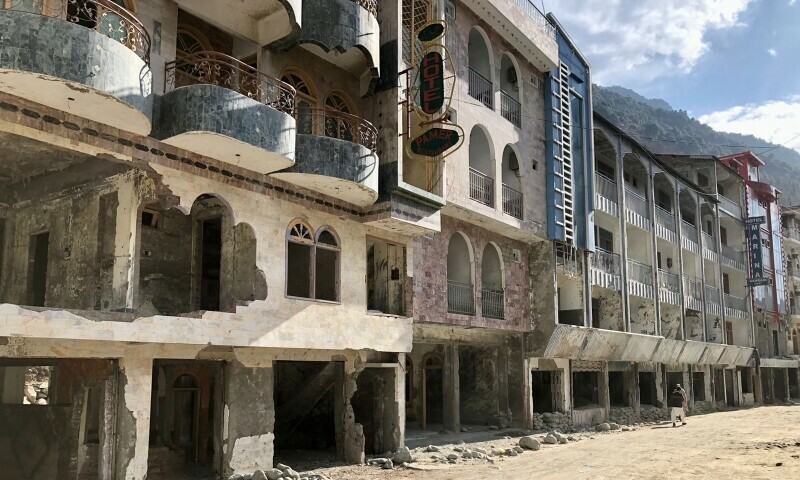

But Torawali pointed out that it was the “terrifying scenes of the Bahrain Bazar” that “are killing us every day”.

“Three months have passed. Every day we cross this place — which is one of the most beautiful markets in Pakistan — and see the devastation,” he said, recalling that the place was once nicknamed “Calle Barcelona”. “But now it looks like a scene from a Hollywood horror movie.”

He went on to say that this was not the first time a calamity of this magnitude had hit the province. This, he claimed, happened during the 2010 floods as well. “But it seems like the government has learned nothing. All it does is beg for money.”

Govt demands climate compensation

Torawali’s statement refers to the compensation that the government is seeking from the world to help Pakistan deal with the climate crisis.

In his debut speech at the UN General Assembly earlier this year, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif raised the concern that Pakistan was among the world’s top climate-vulnerable countries without contributing even 1pc to global emissions.

“Why are my people paying the price of such high global warming through no fault of their own?” he had said, simultaneously warning that “what happens in Pakistan will not stay in Pakistan” in the coming years.

Meanwhile, Climate Change Minister Sherry Rehman told the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference — which was held in November — that “vulnerability shouldn’t be a death sentence” as she pleaded the case for a loss and damage fund for developing countries affected by the climate catastrophes.

The two-week convention, which was otherwise fruitless, saw the signing of an agreement to create a ‘loss and damage fund’, the purpose of which will be to help vulnerable countries combat the challenges of climate change.

Head of agriculture for the government’s climate change research centre and scientist Arif Goheer — who accompanied Rehman to COP27 in Egypt — told Dawn.com that Pakistan, through arduous efforts and consistent pushing, “remained successful in improvising the COP presidency and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in establishing the loss and damage fund.

He said that the fund will be used by the government to build more “climate-resilient” infrastructure and communities.

“This assistance can be earmarked for stronger river embankments, updated water infrastructure, more resilient building material, and early warning systems,” Goheer added.

While the development was hailed as “landmark” in Pakistan, for Torawali it was mere words that disappear in a puff of smoke. “What do I do with them? Will they bring back our dead? Will they repair our ravaged houses?”

Why does Pakistan flood so often?

Floods are a regular feature of Pakistan’s landscape. The first recorded super flood in the country was witnessed in 1950, followed by 1955, 1956, 1959, 1973, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1981, 1983, 1984, 1988, 1992, 1994, 1995, and then every year since 2010.

World Wildlife Fund Senior Director Mashood Arshad explained that riverine flooding —when the water level in a river, lake, or stream rises and overflows onto the neighbouring land — occurs in the country along major rivers every year.

The annual snow melt and monsoons contribute to this flooding.

“Secondly, we have flash flooding via hill torrents which particularly impacts areas such as Dera Ghazi Khan, Dera Ismail Khan, and parts of Balochistan along the Koh-i-Sulaiman mountain range,” Arshad told Dawn.com.

He said that in the last few years, flooding episodes have exacerbated due to climate change which results in intensified rainfall events in riverine watersheds as well as plains.

AN example of this, the WWF director went on to say, was evident from the exorbitant amount of rainfall Balochistan and Sindh received this year.

According to data from the Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD), Pakistan received 190pc more rainfall during the monsoon season this year; Balochistan and Sindh received 430pc and 460pc more than average rainfall, respectively.

Environmentalist Sara Hayat, while explaining the reasons for this change, told Dawn.com that Pakistan’s location in the Global South makes it vulnerable to the rapidly changing monsoon patterns.

“For example, this time, the monsoons came from a different direction and we really couldn’t have forecast them. And then there were so many more monsoon cycles; almost seven to eight as opposed to three to four that we generally get,” she elaborated.

But while climate change is to be blamed, undoubtedly, so are the government and people.

WWF’s Arshad believes that Pakistan’s development trajectory is “haphazard” in nature. “Our infrastructure development is not aligned with proper land use and planning and does not account for multi-hazard risk in vulnerable areas.

“From KP to Karachi, buildings and housing societies have crept up everywhere, often blocking the route of the water flow. And this results in increased losses when floods hit.”

Hayat concurred. She blamed illegal constructions on riverbeds. “If you are going to construct on riverbeds, and floods come or water levels rise, then naturally that construction will do damage […] the way you saw in Swat how entire rest houses and hotels came down this year.”

Another reason for the massive losses during floods that the environmentalist pointed out was Pakistan’s population.

“Natural disasters, themselves, are not harmful until and unless people, property and, in our case, agricultural land is affected. And this damage occurs because we don’t control our population, which makes us very vulnerable to natural disasters.”

Low literacy and poverty were also some of the factors highlighted by the environmentalists.

What are we doing wrong?

Dr Noman Ahmed, urban planner and chairman of the Department of Architecture and Planning at the NED University, said that the development of any infrastructure in Pakistan — from dams to roads and even bridges — is done in isolation of realities.

“Important considerations such as topography and drainage are not taken into account in most cases, leading to the failure of projects,” he told Dawn.com.

“Take our roads for example […] they are practically handicapped when it comes to water drainage. Most of our roads are built at a height and don’t have space for drainage.”

Similar was the case with the left and right bank outfall drains — the drainage canals that collect saline water, industrial effluents, and floodwater from the Indus River basin.

“Megaprojects built along the drain have caused enormous amounts of damage and become a barrier in drainage,” the NED professor said, adding that local influentials alter the infrastructure for their personal benefits, such as creating breaches in canals so that water flows into other fields.

Moreover, he went on to say, rivers have several edges or common wet paths. “People think edges can be used for construction, but they are wrong.

“A river’s highest edge point — the land affected during the highest level of flooding — should not be used. But unfortunately, people build houses there and other buildings,” Dr Ahmed explained.

He said that kachay ke ilaqay [riverbeds] should also not be used because they stop the water flow. But we see cultivation and settlement in these areas, the professor regretted, and held the authorities responsible for these shortcomings.

“They need to ensure that these areas are not used. However, here political influence is very visible. Instead of maintaining technical merit, authorities fall under the influence.”

What can we do right?

WWF’s Arshad believes that Pakistan does not need to reinvent the wheel, but just look at the recommendations that have emerged out of past climate catastrophes.

“We need to strengthen our Met department so that we can be more aware of the potentially extreme weather events, which will strengthen our early warning systems,” he told Dawn.com.

Most importantly, the environmentalist stressed, “we need to allow rivers to flow freely wherever possible”.

“The Indus River system has become an engineered system that is unfortunately not resilient enough to account for the climate crisis. We need to focus on nature-based solutions by allowing natural vegetation to serve as a buffer when flood waters rise.

“Our cities are turning into heat islands without tree cover and vegetation. Hence, there is a need to ensure that open spaces are present in our urban areas and where possible, indigenous trees and vegetation should be utilised,” he added.

Moreover, Arshad said that the government should conduct a risk assessment of all districts via geographic information systems and satellite imagery to identify points of possible intervention. “After that, hydrologists, geographers, and natural resources specialists should be involved in developing plans of action that cater to specific needs of each locale.”

Meanwhile, NED’s Dr Ahmed highlighted three primary steps that needed to be taken. Firstly, provincial authorities need to be equipped to identify areas where development and housing should be prohibited.

“Take Balochistan for example. During the floods this year, the authorities were helpless.”

Secondly, he pointed out, annual surveys should be conducted to identify buildings and structures that need support and rehabilitation.

Thirdly, the professor said that qualified and capable professionals should be brought into the picture. “The people working in these areas presently are not equipped with capacity building.”

Dr Ahmed elaborated that these people could include engineers and architects who could reach out to the local communities and work with them.

“You see, what we are talking about right now, a single government body or agency cannot do it alone,” he said, adding that here the chemistry between the federal government and provinces plays a big role.

“The centre acts as an adviser or policymaker, while provincial and local governments are empowered when it comes to working on the ground level. While differences may exist, we need better synergy in these areas.”

A very small example that the urban planner gave was that of the Council of Common Interests where he said chief ministers of all the provinces could be called to discuss climate-related rebuilding and rehabilitation.

Separately, the government could also take universities on board that have expertise in dealing with disasters and they can work under the planning commission.

Ahmed also criticised the government’s message to the international community. “It is just asking for money when most of the work that needs to be done is related to human resources.”

The way forward

However, apart from seeking climate compensation, the government has a number of plans up its sleeve to ensure the “greening” of development activities, scientist Goheer told Dawn.com.

“It is taking up all the possible intervention at policy, programme and grass-root level to minimise the carbon footprint of the country, besides improving its resilience to growing climate change challenges.

He listed some of Pakistan’s climate mitigation efforts:

- Transition to 60pc share from renewable energy by 2030 and efforts on increasing energy efficiency

- By 2030, 30pc of all new vehicles sold in Pakistan will be electric

- Continued investments in nature-based solutions through afforestation programmes and carbon sequestration projects

- Global Methane Pledge — Pakistan signed the pledge during COP26, agreeing to cut methane emissions by 30pc by the end of this decade

- Efforts on pollution control

Goheer also said that the government, with the support of developing partners, was developing a Resilient, Recovery, Rehabilitation and Reconstruction (4RF) aiming to guide the recovery and reconstruction of Pakistan from the 2022 floods.

“As climate change accelerates the severity and frequency of disasters, institutional reforms and investments must go beyond business as usual and instead, build back better and build systemic resilience. The 4RF is a critical starting point to ensure transformational measures are taken for a resilient recovery, so the disaster will not have multi-generational impacts through the reduction of developmental gains,” he explained.

At the same time, he added that the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) was working on updating the national disaster management plan.

from The Dawn News - Home https://ift.tt/Si8vwhF

0 Comments